INTRO: Gary is the master gunsmith in the Department of

Historic Trades and is currently serving as the

interpretive planning teams coordinator in the

Department of Interpretive Development. The following is

extracted from a manuscript on guns and gunsmiths that

is to be published in the not-too-distant future.

________________________________________

Early settlers and pioneers in America faced an immense

wilderness unlike anything they had experienced in

Europe. As frightening as this vast forest filled with

strange beasts must have been to the first immigrants,

it was also a "sportsman's paradise.'' Author Samuel

Johnson noted that "hunting was the labor of the savages

of North America, but the amusement of the gentlemen of

England." While hunting was a necessity for the Indians

and for the settlers along the frontier, it soon became

an important form of amusement in this country as well.

In England and most of Europe, legal hunting was

controlled by the wealthy because wild game was

considered the property of the landowner. Colonists

found that Indians had a completely opposite view: to

them wild game, like air and sunshine, was a resource

free for the taking. While the colonists did not adopt

completely the Indians' philosophy, it may have

influenced their thinking. Before 1640 a colonist wrote,

"wee accounte of them as the Deare in Virginia—

things belonging to noe man." Beginning with a law

enacted in 1632, which prohibited the killing of wild

hogs and set a bounty on wolves, wild animals in

Virginia became public domain. As such, their use was

subject to control by the government rather than by the

landowners.

With wild game on unoccupied land free for the taking,

the colonists were more likely than their European

counterparts to own hunting guns and to become skilled

in their use. In 1705, Robert Beverly commented in

The History and Present State of Virginia that "the

people there are very skillful in the use of Fire Arms,

being all their Lives accustomed to shoot in the Woods."

The reputation and tradition of Americans as gun owners,

hunters, and marksmen can be traced, at least in part,

to the decision in Jamestown that wild game belonged to

no one man.

In 1739 John Clayton of Gloucester County described

hunting in Virginia to a friend in England:

"To satisfie the Gentlemen you mention who is

desirous of knowing the diversion of hunting and

shooting here and the several sorts of game. ...

Now the Gentlemen here that follow the sport place most

of their diversion in Shooting Deer; w'ch they perform

in this manner they go out early in the morning and

being pritty certain of the places where the Deer

frequent they send their servants w'th dogs to drive 'em

out and so shoot 'em running, the Deer are very swift of

foot the diversion of shooting Turkies

is only to be had in the upper parts of the Countrey

where the woods are of a very great extent,... the

shooting of water fowl is performed too in the same

manner w'th a Water spaniel, as with you,... the bears,

Panthers, Buffaloes and Elks, and wild cats are only to

be found among the mountains ... and hunting there is

very toilsome and laborious and sometimes dangerous."

Another description of deer hunting comes from Colonel

George Hanger, a British officer who was invited on a

hunt in South Carolina after the siege of Charleston. He

explained the popular sport of "fire hunting at

night." Burning pine knots were carried in a

long-handled frying pan balanced on the hunter's

shoulder as he rode slowly through the woods. The fire

was behind the hunter, and it illuminated the deer's

eyes as it stared toward the light. For this method, a

smoothbore gun loaded with buckshot was the best choice

because a spread of pellets gave the greatest certainty

of a hit.

Deer hunting by the more conventional methods of

stalking and trail watching required a more accurate

firearm. The first of these firearms were made in

Germany before 1500 by cutting spiral grooves inside the

barrels to give the ball a spinning motion along its

line of flight. The grooves, or rifling, in the bore

allowed the hunter to fire a round ball accurately. (The

English word "rifle" comes from the German word

riffeln, meaning "grooved.") A skilled marksman

could hit a four-inch circle at a hundred yards with

such a gun. Throughout Europe, rifles became the most

popular guns for hunting big game, from deer to wild

boar.

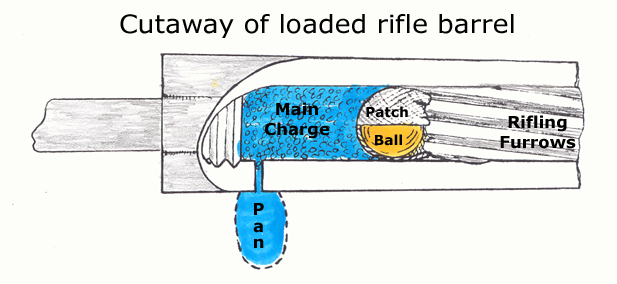

Cut away view of a loaded rifle barrel showing, from

left to right, the threaded breech plug, powder, patched

ball, and rifling grooves. The flash pan, from which the

charge is ignited through the touch hole, is shown by

the dotted lines.

The colonists made and used rifles based on the German

long-barreled "stalking rifles" with English and French

design influences. Many regional styles of rifles

evolved in America after the 1750s. They were produced

in all the populated areas, but more seem to have been

made in Pennsylvania because of both the German

influence and the huge number of immigrants who came

through Philadelphia. This has led to the myth that

rifles were invented in Pennsylvania and the mistaken

use of the term "Pennsylvania rifle" for all rifles of

this type regardless of their place of manufacture.

Rifles made from the Carolinas to New England differ

only in stock architecture, or shape, and in decoration;

students of these "American long rifles" often can

pinpoint the area and date of production from these

details. By the last quarter of the eighteenth century

American rifles had evolved into a form well suited for

the sport of hunting and the necessity of survival, and

their production continued well into the era of

breech-loading cartridge guns.

In addition to his rifle, a hunter needed other

specialized equipment. A powder horn could be purchased

from a horner or made by the hunter himself. To ensure

the correct powder charge for loading, a powder measure

was made from the tip of a deer antler or a tin measure

could be purchased. Bullets, round lead balls, were cast

in a mold that resembled a pair of pliers and, because

the rifle bores were not standardized, each rifle had

its own mold. To carry his bullets, spare flints, and

powder measure, a hunter wore a small leather pouch

attached to a strap. The powder horn and a knife might

have been attached to this shooting bag strap as well.

Unlike other leisure time activities, hunting had a

benefit beyond recreation. It provided food for the

hunter's table. Evidence of the popularity of venison is

found in the recipe books of the period and in the bones

that archaeologists have retrieved from trash pits.

Roast venison was a favorite tavern dish and at least

one Williamsburg resident, Thomas Everard, ordered a

"Venison Pastry Pan"in 1773.

Hunting for sport and for the table was not limited to

deer. Robert Beverly wrote in 1705, "As in summer the

Rivers and Creeks are fill'd with Fish, so in Winter

they are in many Places cover'd with Fowl.... I am but a

small Sports-man, yet with a fowling Peice, have kill'd

above Twenty of them at a Shot."

The "fowling piece" was a smoothbore, without rifling,

designed to fire shot, small lead pellets. Today this

type of sporting gun is called a shotgun. Fowling pieces

of the colonial period ranged in size and weight from

"duck guns" with barrels over five feet long and

weighing more than twelve pounds, to "Bird guns" with

small bores and weighing less than five pounds. The

heavy guns could fire larger charges of shot and powder.

To kill over twenty fowl with a shot, Mr. Beverly

probably used one of these. Medium-weight guns were more

common because they could be loaded with a variety of

sizes of shot to shoot game from buck to quail,

answering the hunter's every need.

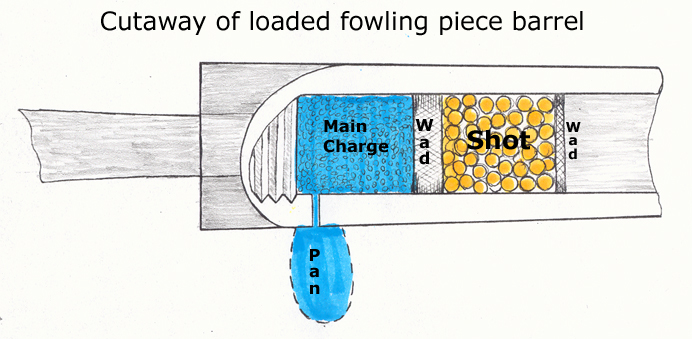

Cut away view of a loaded fowling piece barrel showing,

from left to right, the powder, wadding cardboard (to

transmit the force of the burning powder to the shot),

shot, and more wadding (to prevent the pellets from

rolling out of the barrel before the gun is discharged).

Whether hunting for sport and food or to protect their

crops and livestock, most rural Virginians needed to own

a gun and to become skilled in its use. This was

especially true on the frontier, where Colonel Hanger

observed, "You will often see a boy, not above ten

years of age, driving the cattle home, but not without a

rifle on his shoulder: they never stir, out, on any

business, nor on any journey, without their rifle."

John F. D. Smyth found that frontiersmen always carried

rifles and that "with his rifle upon his shoulder, or

in his hand, a back-wood's man is completely equipped

for visiting, courtship, travel, hunting, or war."

With rifles in almost daily use, both the formal and

impromptu shooting match occurred. Shooting at a mark as

a test of skill began long before the development of

firearms when archers matched their abilities for

prizes. The European tradition of competitive shooting

was well established in the colonies by the eighteenth

century. When Queen Anne came to the throne in 1702,

part of the celebration held in Williamsburg was a

shooting match sponsored by the governor. "The prizes

consisted of rifles, swords, saddles, bridles, boots,

money, and other things." Francis Michel, a visitor from

Switzerland, reported this match and its conclusion: "When

most of the shooting was done, two Indians were brought

in, who shot... so as to surprize us and put us to

shame."

In his book, Early Settlement and Wars of Western

Virginia and Pennsylvania, written in 1824,

the Reverend Dodderidge described frontier shooting

matches from the 1770s:

"Shooting at marks was a common diversion among the

men, when their stock of ammunition would allow it. ...

The present mode of shooting off hand [standing up] was

not then in practice. This mode was not considered as

any trial of the value of a gun; or, indeed, as much of

a test of skill of a marksman. Their shooting was from a

rest, and at as great distance as the length and weight

of the barrel of the gun would throw a ball on

horizontal level. Such was their regard to accuracy, in

these sportive trials of their rifles, and their own

skill in the use of them, that they often put moss or

some other soft substance, on the log or stump from

which they shot."

In addition to formal or competitive shooting, shooting

also occurred during celebrations and on holidays. A1655

law prohibited shooting at "drinkeings" except

for weddings and funerals because it was a waste of

powder. The 1661 version of this law exempted only "buryalls."

In Williamsburg the king's birthday and other holidays

were celebrated by the firing of both small arms and

cannon. Before the telephone only the report of a gun

could share the joy of Christmas morning with distant

neighbors.

In addition to man's natural urge to compete was his

desire to collect fine things. European nobility often

had extensive arms cabinets, and this tradition

continued in America with the wealthy owning firearms as

curios and art objects as well as for use. Part of Lord

Dunmore's collection survives and is on exhibit at the

DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Gallery. Estate

inventories that include old or very old guns suggest a

collection of family heirlooms rather than arms needed

for use. Sometimes just the number of firearms in an

estate inventory(such as that of Ralph Wormeley who had

twenty-one in 1702) indicates an exceptional interest in

guns.

Today, collecting antique guns and their accoutrement is

divided into highly specialized fields. . Some

collectors seek out guns made in a particular area,

while others look for associations with historic events.

Most collectors see another value as well. Their

collection provides a link across time with the men who

used the guns: a feeling of kinship and an understanding

of the bond between a man and his gun in early America.

(top)

|

![]()