|

Wallace Gusler is a native Virginian who grew up in Fort Lewis

Hollow at the foot of Fort Lewis Mountain in Roanoke, County.

Living practically in the shadow of Andrew Lewis’s French and

Indian War fort could have been what sparked Wallace’s interest

in the frontier and longrifles but it wasn’t. Despite their

name, Fort Lewis School largely ignored this local history.

Instead it was the “arrowheads” that he found in plowed fields

that inspired Wallace’s fascination first with Indians, then

with the Virginia frontier.

In about 1954 Wallace’ father, Lester Gusler, decided to replace

a family longrifle burned in a house fire years earlier. He

purchased a full-stocked, iron-mounted, .32 caliber, squirrel

rifle and, when he had trouble getting the old percussion rifle

to fire, Wallace asked if he could try it. Mr. Gusler handed it

over and, as they say, “the rest is history.” While many events

come together to shape the direction of a person’s life, having

that rifle to shoot and hunt with had a huge influence on

Wallace and this writer, who was at the time his neighbor.

Like most folks living in the country, the Guslers had a small

workbench in one of their outbuildings and a few hand tools so

Wallace had a place to start work. By age 14 (1956), he had made

his first muzzleloader, a cherry stocked percussion pistol.

There were, of course, no “how to” books or videos so he began

to visit with some of the old timers in the area, picking their

brains for information and studying any old rifles they had.

Sorting out the folklore from the facts was mostly a matter of

experimentation—one fellow swore that mainsprings had to be

quenched in blood.

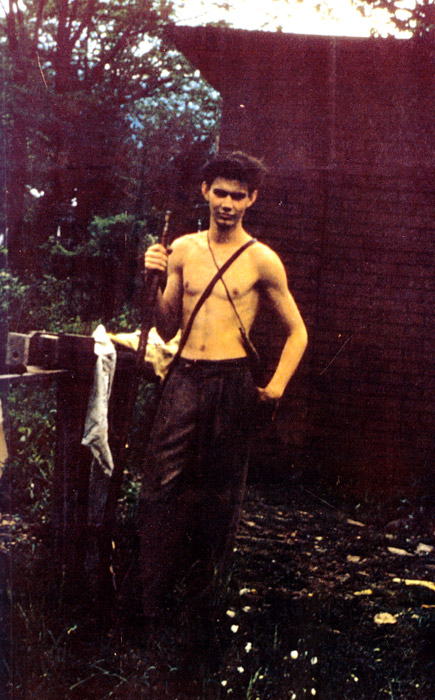

About 1957, Wallace converted the tar paper sided chicken coup

shown in the picture into a workshop. After tearing out the

roosting poles and shoveling out the droppings he added glass

windows and a concrete floor. Although Wallace worked long hours

in this shop, he was not yet a full time gunsmith. He also

worked at his father’s saw mill, tended the garden and

livestock, and ran on the high school track team. In the summer,

hardly a day went by that there was not some excuse to fire a

few shots from the shop into the sawdust pile backstop or at any

blackbirds foolish enough to land within range. In the fall

Hickory Flats in Buck Hollow was a favorite place to camp and

squirrel hunt. There was mountain humor in both those place

names because the Flats were on a steep mountain side and the

last buck was probably killed before WWI. In those days you

could hunt for a week just to find a deer track on Fort Lewis

Mountain.

It was in 1958 that Wallace first visited Howard Sites, a

gunsmith in Covington, VA. Howard was the last working gunsmith

in family of Virginia gunsmiths that began with George Sites in

the Shenandoah Valley about 1785. Howard worked primarily on

modern rifles but his shop held a collection of longrifles and

barrels of old parts. Wallace got his first original carved

rifle in trade for work he did for Howard. That fall Wallace

killed his first buck with a longrifle made by J. J. Henry about

1830.

Soon word of the young gunsmith’s work spread and people began

to bring in all types of guns for him to repair or restock. At

one time $15 would get a new stock for an L.C. Smith double

barrel shotgun and $100 a longrifle—with Wallace supplying all

the parts. His shop also became a hang out for the other

neighbor boys, and men, interested in guns and hunting. In about

1959 the Roanoke Times printed an article about Wallace and his

work. One of those who read the article and came to see the work

was Robyn Hale. A geology student at nearby Virginia Tech, Robyn

was from Tennessee and helped Wallace connect with a larger

circle of shooters and builders. Wallace went to shoots at

Charlie Heffner’s near Franklin, TN and at Leonard Meadow’ shop

in Shady Springs, WV. At the time neither Wallace nor Robyn knew

how their friendship would end up changing Wallace’s life, but

more on that later.

By 1960 a couple of the boys hanging around the shop had also

started building rifles. A revival regional style had developed

that incorporated features of the antique rifles available for

study and what could be seen in the occasional magazine article.

Because many of the old rifles brought in for repair and in

local collections were made in the area, the new guns made in

Wallace’s shop had a strong Virginia feel. This “Fort Lewis

Holler” school of rifle design evolved before we ever saw Joe

Kindig’s groundbreaking 1960 book Thoughts on the Kentucky Rifle

in it’s Golden Age.

Cash was scarce and that made parts hard to come by. Old barrels

were either “freshed out” or re-bored for use. Stocks were made

from boards sawn at his father’s steam powered mill. There were

no good quality flintlocks available so Wallace began to forge

his own. As I remember, most of the guards and buttplates came

from Dixie Gun Works. Fueled by R.C. Colas, Moon Pies and, at

night, country music from WCKY out of Cincinnati, Wallace became

a rifle maker.

About 1962 in front of old chicken coop workshop.

In 1962 Robyn Hale was working for the Virginia Highway

Department and was assigned to a project in Surry County, VA.

Surry is just across the James River from Colonial Williamsburg

so Robyn came to visit. He learned that there was interest in

adding a gunsmith to the small Craft Shops program. Who better

than Wallace?

After a failed attempt for Wallace to meet with Earl Soles, Jr.,

the Assistant Director of Craft Shops, at the Richmond gun show,

Robyn borrowed Wallace’s latest rifle and brought it to

Williamsburg. The rifle was examined, disassembled, and examined

some more. Soon Earl was on his way to Southwest Virginia to

meet Wallace. After an interview that revealed not only a talent

for gun building but also a passionate interest in Virginia

history, Wallace was offered a job. He would start in the

blacksmith shop while a gunsmith shop was set up. He came to

Williamsburg late in 1962. About a year later he moved to the

gunsmith shop and in 1964 was named Master Gunsmith.

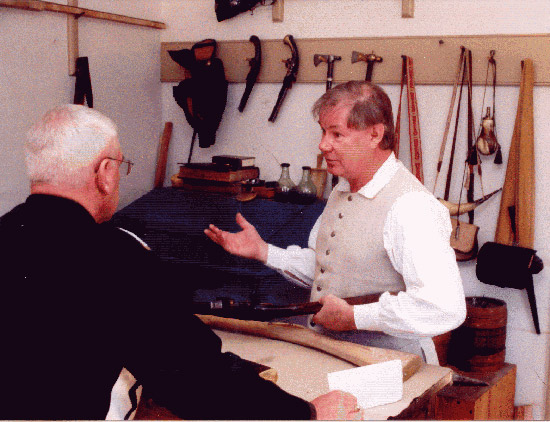

One of the goals that were evolving for the Colonial

Williamsburg’s trades program in the 1960s was for each shop to

rediscover and preserve the skills and period technology of

their trade. Rediscovery of lost processes and techniques

requires both research and experimentation. In the museum world

this combined process is now known as experimental or “above

ground” archaeology.

When he came to Williamsburg, Wallace could make every part of a

rifle by hand, except the barrel. He set out to rediscover the

process of hand forging rifle barrels. Written descriptions of

the process existed and a few old timers remembered seeing it

done in the 1890s, but no one could be found who had actually

done the work. Examination of old rifle barrels revealed that

most had a single seam running lengthwise instead of the spiral

seam found on pattern welded shotgun barrels. Acid etching also

showed that most were butt, rather than lap, welded. Knowing how

something was done and actually being able to do it are two very

different things. By 1964 Wallace was ready to begin teaching

himself to forge weld rifle barrels.

In 1965, I had completed my first year of college and Wallace

offered me a summer job. I eagerly accepted because it was a

chance to get paid for doing what I considered my hobby and to

help him learn how to weld rifle barrels. (Twenty years later,

when asked how I came to work in Williamsburg, I would tell

visitors that it was a hobby that got out of hand.) That summer

we were faced with an interesting situation. The shop was open

to the public from 9 a.m. until 7 p.m. and during the day our

time was divided between working on guns and talking to visitors

about the trade. The forge was next door in the blacksmith shop

and in constant use making items for sale. Wallace and I had to

experiment with barrel welding after both shops closed.

Fortunately using the facilities and tools after hours was

permitted and even encouraged as a way for apprentices to build

their skills.

Because visitors were often on the street, we had to work with

the doors and shutters of the blacksmith shop closed. That

required us to hang up jury-rigged electric lights—three naked

150-watt bulbs cast harsh shadows. If you have ever been to

Williamsburg in the summer you know that the heat and humidity

can be intense, both often in the ninety’s. Working at a forge

in a closed shop was a physical challenge but we did it

enthusiastically on many nights that summer. It was a time of

excitement and discovery.

We had no wrought iron and had to use mild steel for those first

efforts. That made the welding more difficult because steel

tends to burn if even slightly overheated. I remember picking up

a partially welded skelp only to see half of my barrel left in

the fire. In a careless moment I had burned it. Lesson learned,

managing the fire is as important as knowing how to hammer.

There were other setbacks, but, by summer’s end, Wallace had the

hand-forged barrel that he used to build his first totally

hand-made rifle later that year.

Wallace had become the first person in modern times to recreate

all the processes of making a rifle with 18th-century

technology. In [Terri look up month] of 1966 John Bivins wrote

an article about Wallace and that first handmade rifle for

Muzzle Blasts. During the winter of 1967 Colonial Williamsburg

documented making a complete rifle in the film The Gunsmith of

Williamsburg. Released in 1968, this 58-minute film is still the

best selling video of the trades series.

In 1972 Wallace left the Gunsmith Shop to become the Curator of

Mechanical Objects. Two years later he became Curator of

Furniture. In January of 1985, Wallace transferred to the

Department of Conservation as Chief Conservator, Furniture and

Arms, and in June of 1987, he was promoted to Director of

Conservation. Although he was away from the shop, Wallace

continued to teach classes on carving, engraving and arms

conservation and to build rifles at his home shop. He also

expanded his work to include architectural carving, making

period furniture and doing sculpture. And, all the while,

research and photography continued for a book on Virginia

gunsmiths and their work.

In the spring of 1994 Wallace returned to the position of Master

Gunsmith, working part of each week in the shop and part on his

Virginia gunsmith book. As his expected retirement date began to

draw near Wallace was given a leave of absence to work full time

on his book. The rifle whose photos accompany this article is

the last all handmade rifle Wallace produced for the Colonial

Williamsburg Gunsmith Shop. It was completed last spring.

After over forty years with Colonial Williamsburg, Wallace will

retire this winter. Retirement does not mean he plans to

quite working. There are many projects to be completed,

including his book. You will also find him teaching classes at

the NMLRA Gunsmithing Seminar at Western Kentucky University. In

anticipation of having more time for doing custom work Wallace

has opened a booth on rifle maker’s row at Friendship. Stop by

and say hello to the man whose work lead the way in the revival

of traditional rifle making and whose research and writing

continues to expand our knowledge of the rifle and the culture

in which it was used.

(top) |

![]()