|

What distinguishes a “Virginia rifle” from any other

American made rifle from the same period?

Although we see the term “Virginia rifle” used widely by

modern rifle builders and dealers, there is no single or

even group of details that would define a style of rifle

that spans so many different “schools” or regional

styles. In parts of Virginia, just like in Pennsylvania,

Maryland, and the Carolinas, rifles were an important

part of the material culture. Rifles were often locally

made and this lead to the evolution of regional styles

that can sometimes be attributed to an area, a county, a

town, or even a particular shop. This regionalism is not

unique to rifles. Experts can identify local styles in

nearly all hand crafted objects from furniture, to

quilts, to pottery.

Regional styles in firearms are not limited to America

either. Not too many years ago all Germanic rifles were

lumped together by the average longrifle collector or

builder as simply “Jaegers.” Now we know that there are

many different regional styles there as well.

If

we took the simple way out and just said that all rifles

made in Virginia were “Virginia rifles” that would cover

a huge geographical area. Unlike Pennsylvania, Maryland,

and most of New England, whose western boundaries were

established by their colonial charters, Virginia

extended westward to include the territory that later

became Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, etc. (In the

early 17th century the English claimed its

boundary went west to the Pacific Ocean.) Until the

Civil War it also included what is now West Virginia.

Evolution of the Counties of Virginia 1617-1995

(link to RootsWeb interactive maps--click on year to

change map)

What did a rifle made in Virginia prior to 1750 look

like?

The

question about what a pre-1750 longrifle might look like

goes WAY beyond Virginia. Documented American rifles

made anywhere before 1760 are scarce and, if you toss

out the ones with questionable documentation,

signatures, or origin, they come down basically to a few

parts found in archaeological sites, also sometimes of

questionable, European or American, origin. Based on

documents, we know that both short rifles and long

rifles existed in the colonies prior to the 1740s but

nailing down a few surviving examples would be a

wonderful breakthrough in research.

Given the lack of pre-1750 examples, what does it mean

when someone refers to a longrifle as “early?”

“Early” is another term that has different meanings

depending on the context in which it is used. An early

Tennessee rifle is very different in period from an

early Lancaster rifle. For the sake of simplicity I will

stick to how the term is generally used in reference to

the subject of Virginia made longrifles.

An

early style rifle usually means one that pre-dates the

“Golden Age” rifles but using that definition simply

replaces the first question with, “What is a Golden Age

rifle?” For the answer to that I refer you to page 31 in

the third chapter of Joe Kindig’s book Thoughts on

the Kentucky Rifle in Its Golden Age (1960).

Rifles actually made before the Revolutionary War are

certainly early, not to mention scarce, and most will

agree that the term also applies to those made during

and immediately after the war. If you agree with me on

that loose definition of the term, any rifle made prior

to ca. 1780-85 is an “early rifle.”

But

there is more to the definition of an early style rifle

than the year in which it was made. The previously

mentioned chapter in Mr. Kindig’s book addresses many of

the characteristics that define an early rifle—wide flat

butt pieces, tapered and flared barrels, etc. Chapter 20

in Volume II of George Shumway,s Rifles of Colonial

America (1980) looks more closely at the evolution

of the art on longrifles with an eye toward the shift

from baroque to rococo design elements. Both the form of

the rifle and the art on it are part of what a collector

refers to when he refers to a rifle as “early.”

For

a modern builder who aspires to produce an early rifle,

Virginia or otherwise, there is one simple rule for

dating objects to keep in mind: no rifle can be earlier

than the latest detail of its construction or

decoration. Examples— since “German silver” (a man made

nickel-brass alloy) did not come into use until the end

of the first quarter of the 19th century, a

rifle with German silver mounts or inlays could not

considered a historically correct 18th-century

rifle. Likewise a Federal Eagle on an inlay or patch box

dates the rifle to the mid-1780s or later. Those

examples are simple and obvious. Learning to tell the

difference between rococo and Neo-classical design

elements requires more study but is every bit as

important to doing historically correct work.

Since Williamsburg was the capital of Virginia during

much of the colonial period, what was a rifle made there

like?

On

the question of Williamsburg rifles of the 18th

century the answer is simple: there are no know

examples. Tidewater Virginia was not really part of the

“rifle culture” that grew up west of the Blue Ridge

Mountains. A few people in eastern Virginia owned rifles

but they were probably imported from England or brought

there from other regions.

In

Williamsburg, there are some unfinished parts from the

Geddy site that lets us know they were probably making

pistols and fowlers. (The blank sideplate casting

pattern they excavated could have been for a rifle.)

There is documentation that the Geddy brothers were

offering to rifle barrels in 1751 but that is a service

and doesn’t prove they made new rifles.

The

only known surviving civilian firearm signed by a

Williamsburg gunsmith is a screw barrel pistol by John

Brush. Brush came to Williamsburg in 1717 and died in

1726. The estate of Henry Bowcock, who died a few miles

from Williamsburg in 1729, included “1 bird piece made

by Brush.” That lets us know he also made fowlers. [See:

The Gunsmith in Colonial Virginia by Harold B.

Gill, Jr. 1974]

During the time when I was the Master of the Colonial

Williamsburg Gunsmith Shop we made longrifles that

represented those from towns many miles to the west and

north—along the Great Wagon Road. When called on to

produce something that might have been made in Tidewater

Virginia we drew on details from English rifles or work

believed to be from near Fredericksburg at the fall line

of the Rappahannock River.

What is the difference between a “Valley rifle” and a

“Shenandoah Valley rifle?”

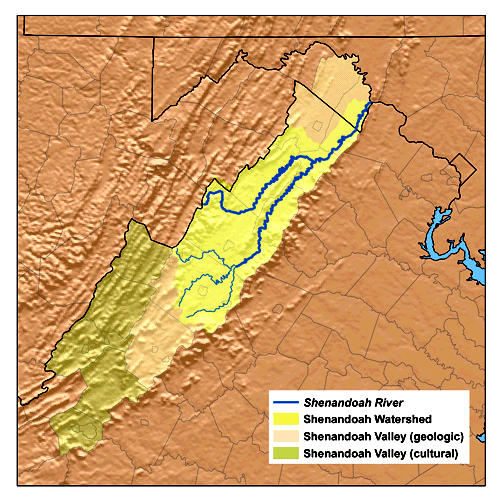

The

terms “Shenandoah Valley” and “Valley of Virginia” can

be confusing because they may be used interchangeably

for the entire valley between the Blue Ridge Mountains

on the east and the Appalachian Mountains on the west.

(See the map below drawn by Karl Musser and displayed on

Wikipedia.) If you drive south down the path of the

Great Wagon Road, along modern Rt.11 and/or I-81, from

Maryland past Winchester toward the Roanoke area you are

in one continuous valley defined by those two mountain

ranges. That large geographic region is all called the

“Valley of Virginia” but only the large northern part of

the Valley, from just south of Staunton, is actually

drained by the Shenandoah’s branches which flow north.

A

rifle made in Staunton by John Sheetz is technically a

Shenandoah Valley rifle but one made by John Davidson in

Rockbridge County is a Valley rifle or, more

specifically, a James River Basin rifle.

What does it mean when a collector attributes an antique

rifle to the “James River basin” area?

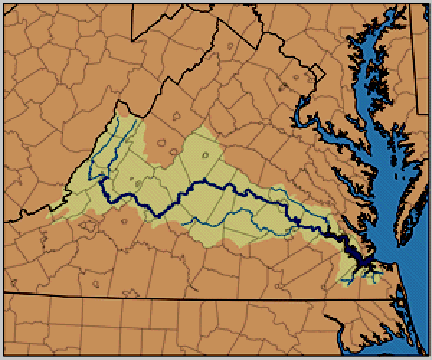

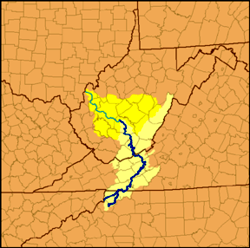

To

a geologist or geographer the entire James River

drainage can be called the James River basin. When

collectors talk about rifle making in the James River

“basin” they are referring to the south-central part of

the Valley of Virginia where the streams drain east into

the James River rather than north into the Shenandoah

River. At the “Forks of the James” the many branches of

the upper James come together and pass through a gap in

the Blue Ridge Mountains near Glasgow, south of

Lexington.

Where do so called Southwest Virginia rifles fit in the

picture?

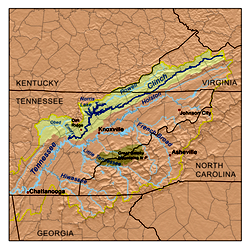

The

crest of the Appalachian Mountain Range forms the

eastern continental divide between waters flowing

eastward into the Atlantic and those flowing down the

Mississippi into the Gulf of Mexico. (In the Kings

proclamation of 1763 he called the latter the “westward

waters” and banned settlement there.) Major eastward

flowing waters in Virginia’s rifle making country

include the Potomac, Shenandoah, James, and Roanoke

Rivers. Between Roanoke and Blacksburg is the divide

where waters in present day Virginia flow west, either

by way of the New River drainage into the Ohio or, even

farther west, down the Holston, Clinch and Powell Rivers

into Tennessee.

In

common usage the parts of Virginia beyond the

continental divide are known as “Southwest Virginia.”

The definition is far from exact and Roanoke County,

which is east of the break, is often referred to as

being in SW Virginia.

The

rifles made in those Southwest Virginia counties include

a number of distinct regional styles. So, just like the

term “Valley rifles,” there is no set of details common

to them all. That said, modern builders and collectors

generally point out that iron mounts are more common on

rifles from this western area than on rifles made in

other parts of Virginia. True, however the answer is not

that simple. There are surviving iron mounted rifles

made from Staunton southward and brass mounted rifles

made well beyond the divide.

The

late flint and percussion rifles made in far SW Virginia

often closely resemble those made in North Carolina and

Tennessee. There is still research to be done to more

clearly define those regional styles within the “over

the mountain” regions and state lines may have much less

to do with the results than mountain ridges and river

valleys.

(top) |