|

Prior to the development of deep hole drilling, most

barrels were made by forge welding a tube and reaming

it. (Brass barrels were core castings.) There are several ways to

weld a tube but the simplest and one most commonly found

on longrifle barrels is a single butt-welded seam

running lengthwise. That is what will be described in

this article.

The first step is to create a skelp from a bar of

wrought iron. The size of the skelp is dependant on the

size barrel but for a 46" rifle barrel 1 1/8 at the

breech it would be about 38" long, 4"wide and

tapering from 1/2 to 3/8 in thickness.

Barrel making demo for a Learning Weekend in

February, 1983

After forging in the desired taper the skelp if "fullered

up" (forged in a swage block with a top tool called a

fuller that is struck by a sledge) to produce a U shape

from end to end.

Beginning in the middle, edges of the skelp are forged

over until the contact each other in an area about 2

inches long. This contact area is heated red hot, so it

will melt the flux. Flux (can be borax or fine sand) is

spooned on both surfaces. The fluxed section is heated

to a welding heat (yellow-white hot with a slight shower

of sparks) and it is brought quickly from the fire to

the swage block. An assistant inserts the tapered tip of

a steel mandrel into the tube and quick hammer blows

fuse the edges together around the mandrel. The mandrel

is only in the barrel a few inches and not for more than

a minute so it doesn't usually stick -- if it hangs a

little it can be snatched out by catching the hooked

handle end on the edge of the anvil.

I usually run at least two welding heats on each section

and don't try to weld more than an inch or so at a time.

(Some period accounts imply that by using strikers with

sledge hammers a team on men could weld several inches

in one heat.) Welding is as much art as science and it

is important to learn the feel on the heat so you can

tell when the weld is sound. I found that getting a

round hole during the welding saved a lot of time

reaming so I began forging the tube down around a

smaller mandrel after the first welding heat.

We pause to examine the weld before returning the barrel

to the fire.

I weld to one end then turn the barrel skelp end-for-end

and weld the other half. Since the skelp was tapered the

resulting tube is heaviest at the breach and has a

fairly even taper. I use a concave top swage to smooth

up the round tube and adjust the taper as needed to

remove any lumps. If a section is undersize to can be

enlarged by "jumping" (heating a section and striking

the end of the tube on the anvil to thicken the hot

part. The flare at the muzzle is also produced by

jumping.

After rounding up the tube it is examined for tight

spots. If there is any constriction of the bore at this

stage the round tube can be reamed with a couple of bits

before it is hammered octagon.

I first forge the octagon with a hand hammer at a bright

red heat. No swage block is involved in this step--just

the flat of the anvil. This is an opportunity to check

for welding flaws because they will show up as shadows

in the tube. Once the rough octagon is formed, the

octagon is refined with a tool called a

flatter. The flatter has a flat face about three inches

square and is struck by a sledge. Keeping the heat at a dull red

during this step will develop a

smooth surface and the corners will be sharper.

UPDATE: American Pioneer Video has

released a one hour and 25 minute video showing the

barrel forging process described here. Jon Laubach, his

son Chris, and Mike Miller are featured. See Jim

Wright's web site at

http://www.americanpioneervideo.com/ .

(top)

This barrel reaming machine was based loosely on

drawings in "The Gunmaker and the Gunstocker" by P.N.

Sprengel, Berlin, 1771 [translated and reprinted in

Journal of Historical Armsmaking Technology, Volume III,

1988]

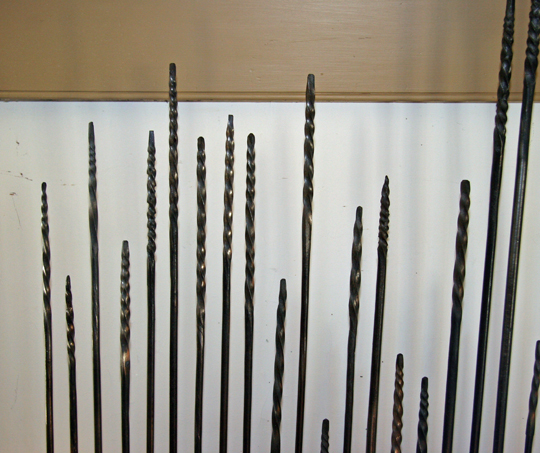

Reaming the barrel begins with a bit that just touches

the tight spots and progresses with larger and larger

bits until the barrel is free of any forged surface.

These rough boring bits are a twisted square that look a

bit like a modern bolt removing tool called an "easy

out." They are turned in the barrel opposite the way

they are twisted so they don't thread themselves into

the barrel and break off. This causes the chips to be

pushed ahead of the bit and requires us to stop

frequently to blow out chips and oil the bit. If a

particular caliber has been ordered it may take even

more reaming to get out near final bore size.

Many sizes of boring bits are required.

These three bits would all be turned clockwise.

The barrel

is straightened as well as possible during the reaming

by removing it from the machine and looking through the

bore. A line of light and shadow reflecting in the bore

will show the bends.

Once the barrel is close to size the final reaming is

done with s single long square bit that is backed on one

face with a thin sliver of wood -- flat on the side

against the bit and rounded to match the radius of the

barrel on the other. Only two corners cut. This bit

takes a very light cut and it is "expanded" by placing

thin paper between the bit and the wooden backing strip.

This reaming is always done from breach to muzzle and

after the final reaming the bore will have a very slight

taper due to the wear and compression of the wood.

Two views of the square reamer and its wooden backing

strip. Only the two corners opposite the hickory strip

cut. As Wallace said in the Gunsmith of Williamsburg

film, "the borings are as fine as face powder."

(top)

Next the barrel is checked for final straightness and

bent as needed. It is then filed to the desired external

taper and flare. The flats are filed in opposite pairs.

For example, the top and bottom flats first, then the

two side flats, then the other four. Once a pair is done

several rings can be filed around the barrel at

intervals to speed up matching the diameter at each

point. Rough filing can be across the flats but the

final filing is by "draw filing"-- holding the file at

90 degrees to the barrel and cutting on the pull stroke.

Slight irregularities are detected by running the file

lengthwise along the flat.

Rifling is simple because the machine controls the

process. Rifling is also done beech to muzzle so the

groves will follow the taper of the bore. I use round

bottom groves. The cutter is pulled through all seven

groves, one at a time, until it stops taking a cut , the

it is expanded by placing a thin paper shim under the

cutter. This is repeated until the desired grove depth is

reached. For a patched round ball the rifling is usually

about .012" to .014" deep in a hunting rifle.

This machine was built in the 1980s. The frame is oak

but the guide and head block are sugar maple for better

wear resistance.

Note the numbers cut on the guide to help track which

groove to cut next.

Four tooth rifling cutter inlet in a bore diameter

hickory rod.

(top)

Thread the breech, plug it, drill the touch hole and try

to blow up the barrel by proof testing it. A period

proof load (in England) for a forged wrought iron barrel

was one patched ball and an equal weight of powder.

(About what some bench shooters use every day!) In

France it was two balls and 1/2 a ball weight of powder.

I recommend buying the video The Gunsmith of

Williamsburg. It was made in 1967 and does not

have all the steps we developed later but it will show

you how a barrel is welded, reamed, and rifled.

Jim

Wright of American Pioneer Video has also produced a new

(2009) DVD that shows the forging in

more detail. Jon Laubach did the forging with the help

of his son Chris.

(top) |