|

The

process of making a curved patchbox hinge has

occasionally come up in discussions, both in classes and

on the web, and in at least one printed source on rifle

making you may have found the statement that a curved hinge will not function.

While it

is true that many original makers did use hinges that

were essentially straight, there are also old rifles

where the hinge is curved to match the shape of the

stock. After making my first rifle with a straight hinge

I decided that curved hinges were more pleasing to my

eye and I have been using them on my rifles since the

late 1960s. I have also taught a few classes on mount

making during the NMLRA Seminars at WKU and show students in

those classes how to make and fit curved hinges.

While

there is no substitute for hands-on, supervised

training, I hope this web page will provide enough basic

information to allow someone wanting to learn to make a

box that matches the flow of their stock to get a good

start on teaching themselves.

________________________________

The steps

involved are pretty much the same for any type of hinge

that is made as part of the sheet metal finial and door

rather than being soldered on. (Cast boxes are made by

several very different processes.)

I have

never mastered the process of making boxes out of the

extremely thin sheet seen on some original rifles or

casting my own sheet brass. Although Wallace

Gusler cast the sheet brass for the mounts in his

Gunsmith of Williamsburg movie, it was a real

challenge and he ended up casting sheet about an 1/8

inch thick and hammering it out thinner. I suspect that

is why cast boxes are often fairly thick and have the

hinges cast in and drilled for the pin.

THE

PROCESS:

I usually

start with sheet brass that is either 16 gauge (.051”)

or 14 gauge (.064”). (The thicker material is what I

would generally use on earlier rifles.) Anneal the brass

and rough out rectangles for the door and finial. I make

them both a bit oversize and don’t bother with any

layout until after the hinges are fit.

For the

hinge pins I have used everything from coat hanger wire

to drill rod. Now I prefer the spring steel wire sold as

“music wire” in many hobby shops and the better hardware

stores. Pick a wire that is as close in diameter to the

thickness of the brass.

A lot of

modern makers like to use some sort of jig or form to

help bend the hinges but I have never seen the need for

any tools other than a hammer and a vise for this step.

While it is true that 18th-century sheet

metal workers like tin and silversmiths used a lot of

dies, I have never found any evidence that a gunsmith

had a special tool for what to me is a very simple step.

Fold the

annealed brass back on itself to begin forming the

barrel of the hinge. The amount of overlap in not

critical and as you will see in later pictures I have

been in the habit of filing the lap inside the box door

into a decorative shape. (I guess you’d call this a shop

detail of the Colonial Williamsburg shop since many of

the rifles made there have some form of this

decoration.)

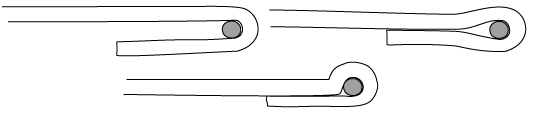

The hinge

is formed around the pin and you need to make sure that

the pin stays all the way out against the inside of the

bend. See the three drawings below. Going from the

second drawing to the third is accomplished by driving

the outside of the hinge down into the correctly spaced

gap between the jaws of a vise. That also thins the

lapped over section a bit as it moves the pin so it

aligns with the sheet of the door or finial. Depending

on how much you have work hardened the brass, it may

need to be annealed again during this to get a sharp

corner where the exterior of the door or finial buts

against the barrel.

Drawings 1, 2, & 3 showing major steps in forming the

hinge around the pin.

Once the

hinge is formed both halves are bent to match the curve

of the stock. Anneal the brass again first. Depending on

the style, period, and length of the door this curve can

vary from slight to fairly pronounced. If the stock is a

form where the wrist carries back into the butt, the

curve may be asymmetrical with a sharper bend in the top

toward the comb. To avoid dinging up the hinge barrel, I

add this bend by hammering on the inside and driving the

brass down into a curve cut in the end grain of a piece

of wood. Hammer marks on interior surfaces are normal in

period work.

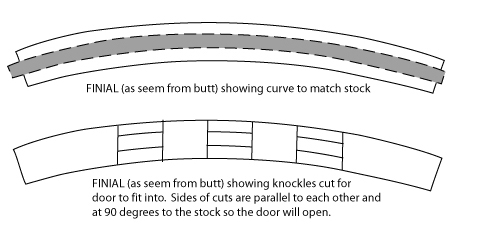

Drawings

four and five show the bent hinge of a finial. The curve

of the door is simply matched to the finial by eyeball.

Now you can pull the pins out of the door and finial.

Drawings 4 & 5 showing the finial hinge curved to

match the stock (pin in gray) and the three female

knuckles cut to receive the door (pin shown but not

colored).

The reason

a curved hinge works is shown in the fifth drawing.

Waiting until after it is bent to cut the knuckles

allows them to be cut perpendicular to the stock and

parallel to each other. All the mating surfaces of the

two halves of the hinge are in the same plane as the

opening motion of the door. If the knuckles were cut

before bending the hinge to fit the stock there would be

gaps at the top and binding on the inside after the bend

was added.

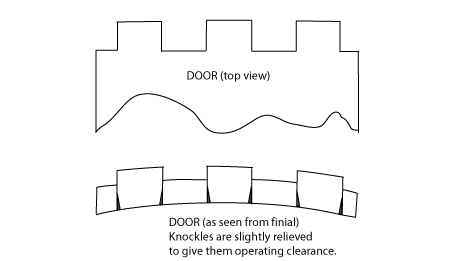

Most of

the boxes I have made have two knuckles on the door but

the number really doesn’t matter. I show three in

drawings 6 & 7 and in the unfinished box below. The 7th

drawing shows a tiny bit of relief cut at the bottom of

each knuckle. These have two purposes; they free up the

hinge to open wider, and they make fitting the door to

the finial easier.

Drawings 6 & 7 -- pin not shown.

For an early rifle a short, wide door and a short

finial could be required. On a wide door three knuckles

are stronger than two.

This blank box was made while I was teaching a class

at WKU and I have never had an occasion to use it.

I make the

door knuckles first then scribe and inlet them into the

finial working from the outside inward. As soon as the

door is in enough for the pin holes to begin to line up,

I file a long taper on the finial pin and drive it in to

draw the door up tightly against the finial. Carpenters

doing timber frame construction use a long steel pin for

this same purpose of drawing joints together but I

cannot recall the name they give the tool.

If it is

fit well the hinge will barely move when first

completely assembled but a little filing on the exterior

and a couple of drops of oil will allow you to work it

back and forth until it moves freely. I save the final

dressing of the outside of the hinge until after it is

inlet in the stock and everything is being filed down to

match the wood and brass.

(top)

Below are some pictures of curved hinges:

This box was made about 1995 and I have kept it as a

demo piece to use in the classroom. Obviously it has

never been on a rifle. The finial is a very stylized

version of a Valley of Virginia "spiral flower." When

finished it would have been similar to this one

valley_rifle.htm

This hinge is more curved toward the comb side

because it was intended for a rifle with the cove of the

wrist carried back into the butt.

This is the box on my current hunting rifle.

2002_rifle.htm

(top) |